L3akCTF - Reverse - babyRev

Just a remap table and vibes.

Challenge description

They always give you strings challenges, we are not the same, we do better.

Find the flag.

By: 0xnil

Flag : L3AK{you_are_not_gonna_guess_me}

Ressources

For this challenge, we were given a 64-bit ELF binary that—as the category name suggests—requires reversing to retrieve the flag.

Tools

I used Ghidra for disassembly and static analysis throughout this challenge. Alternatives like Binary Ninja or IDA Pro would also work perfectly. In fact, no additional tools are strictly necessary; everything required to solve the challenge can be done within your favorite disassembler.

Walkthrough

Initial Analysis

We start by performing a quick inspection of the binary using the file command:

1

2

3

4

$ file babyrev

babyrev: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2,

BuildID[sha1]=d30e77a25a8571ad0c6f336287fe9ce74ea9bb7c, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

As expected, this is a 64-bit ELF file targeting the x86-64 architecture. It’s dynamically linked and built for GNU/Linux. One key detail: the binary is not stripped—which is excellent news. This means that function names and global variables have been preserved, making the reverse engineering process much easier.

Dynamic Analysis

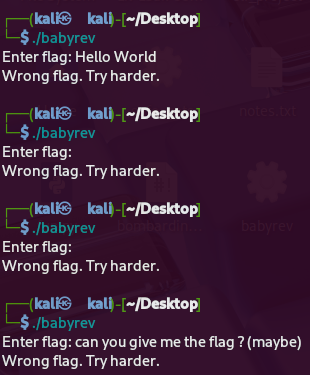

Before diving into the static analysis, let’s observe the program’s behavior by simply running it:

As we can see, the binary prompts us for a flag and returns “Wrong flag. Try harder.” on incorrect input. Classic reverse engineering challenge behavior.

Static Analysis

main() function

Now it’s time to dig into the code. Opening the binary in Ghidra, here’s the decompiled main() function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

undefined8 main(void) {

int iVar1;

time_t tVar2;

size_t __n;

int local_c;

tVar2 = time((time_t *)0x0);

srand((uint)tVar2);

init_remap();

signal(2,sigint_handler);

printf("Enter flag: ");

fflush(stdout);

fgets(input,0x40,stdin);

for (local_c = 0; input[local_c] != '\0'; local_c = local_c + 1) {

if (-1 < (char)input[local_c]) {

input[local_c] = remap[(int)(uint)(byte)input[local_c]];

}

}

__n = strlen(flag);

iVar1 = strncmp(input,flag,__n);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

puts("Correct! Here is your prize.");

}

else {

puts("Wrong flag. Try harder.");

}

return 0;

}

Here’s what the program is doing, step by step:

- Seeds the RNG with the current timestamp using

srand(time(NULL)). This suggests a possible time-dependence, but as we’ll see, it’s not directly relevant to the flag. - Calls

init_remap(), which likely initializes the remap table used later. - Sets up a signal handler for

SIGINT, though this isn’t directly relevant for our solution path. - Prompts the user for input and reads up to 64 bytes via

fgets(). - Iterates through the input and replaces each character with a corresponding character from a remap array, likely acting as a substitution cipher.

- Compares the transformed input with a hardcoded flag using

strncmp()and prints the result accordingly.

At this point, one might be tempted to try extracting the flag variable directly, but that won’t work—because the comparison is done after transforming the user input using the remap table. In other words, the input is encoded, and the flag is the encoded version of the correct input.

Let’s now clean up and simplify our understanding of main():

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

undefined8 main(void)

{

// 1. Variables initialisation

int is_input_equal_flag;

time_t seed;

size_t size_of_flag;

int i;

seed = time((time_t *)0x0);

srand((uint)seed);

// 2. Call the init_remap() function

init_remap();

signal(2,sigint_handler);

// 3. Get user input

printf("Enter flag: ");

fflush(stdout);

fgets(input,0x40,stdin);

// 4. Modify user input using remap

for (i = 0; input[i] != '\0'; i = i + 1) {

if (-1 < (char)input[i]) {

input[i] = remap[(int)(uint)(byte)input[i]];

}

}

// 5. Verify if modified user input equals flag

size_of_flag = strlen(flag);

is_input_equal_flag = strncmp(input,flag,size_of_flag);

if (is_input_equal_flag == 0) {

puts("Correct! Here is your prize.");

}

else {

puts("Wrong flag. Try harder.");

}

return 0;

}

From this, the challenge becomes clearer: we need to reverse the remapping process to reconstruct the original flag input that, once encoded using remap, matches the hardcoded flag.

init_remap() function

To solve this challenge, we need to understand how the user input is transformed before being compared to the hardcoded flag. This transformation is defined in the init_remap() function, which sets up a substitution table called remap. Here’s a cleaned-up version of that function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

void init_remap(void)

{

for (int i = 0; i < 0x80; i = i + 1) {

remap[i] = (char)i;

}

remap[0x61] = 0x71;

remap[0x62] = 0x77;

remap[99] = 0x65;

remap[100] = 0x72;

remap[0x65] = 0x74;

remap[0x66] = 0x79;

remap[0x67] = 0x75;

remap[0x68] = 0x69;

remap[0x69] = 0x6f;

remap[0x6a] = 0x70;

remap[0x6b] = 0x61;

remap[0x6c] = 0x73;

remap[0x6d] = 100;

remap[0x6e] = 0x66;

remap[0x6f] = 0x67;

remap[0x70] = 0x68;

remap[0x71] = 0x6a;

remap[0x72] = 0x6b;

remap[0x73] = 0x6c;

remap[0x74] = 0x7a;

remap[0x75] = 0x78;

remap[0x76] = 99;

remap[0x77] = 0x76;

remap[0x78] = 0x62;

remap[0x79] = 0x6e;

remap[0x7a] = 0x6d;

return;

}

The function starts by initializing remap[i] = i for all values from 0x00 to 0x7F, effectively creating an identity mapping. Then, it redefines mappings for lowercase ASCII characters a to z (from 97 to 122). These values are substituted using a hardcoded mapping that corresponds to the QWERTY keyboard layout.

In other words, the function defines a simple monoalphabetic substitution cipher, replacing each lowercase letter with the letter found in the same position on a QWERTY keyboard:

1

2

3

4

remap[0x61] = 0x71; // remap["a"] = "q" -> "a" becomes "q"

remap[0x62] = 0x77; // remap["b"] = "w" -> "b" becomes "w"

remap[99] = 0x65; // remap["c"] = "e" -> "c" becomes "e"

...

This means that to reverse the process, we just need to invert this substitution: for each character in the transformed flag, we substitute it with the letter that maps to it in the remap array.

Script to reverse remap

Now that we understand the transformation, let’s write a Python script to reverse it and retrieve the original user input that, after remapping, would match the encoded flag:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

ciphertext = "ngx_qkt_fgz_ugffq_uxtll_dt"

qwerty = "qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnm"

alpha = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"

remap = dict(zip(qwerty, alpha))

flag = ''.join(remap.get(c, c) for c in ciphertext)

print("Flag:", flag)

Running this gives us:

1

Flag : you_are_not_gonna_guess_me

And just like that, we have our flag!

Conclusion

It had been a while since I posted a write-up—I’ve been pretty busy searching for an internship for the final year of my degree, which put CTFs on hold for a bit. But I’m finally getting back into it!

This challenge was categorized as beginner-friendly, but I genuinely enjoyed it. Although I don’t usually focus on reverse engineering, this challenge was a great way to ease into it.

Thanks for reading — hope you enjoyed the writeup. See you in the next one!

emree1